Echoing Bertrand

Bertrand “Buddy” Might lived a bright, adventurous, meaningful, challenging and all too brief life. To those whom knew him personally, he brought a sense of calm, happiness and love to all that had the fortune of being in his presence.

His remarkable life leaves behind many echoes, echoes that this site amplifies through articles inspired by his life and legacy:

If you never knew Bertrand, there is a brief recap of his remarkable legislative, digital, communal, medical and scientific legacy below and separate coverage of his life and final months by Casey Ross at STAT News.

If you want to actively accelerate his legacy of science in the service of patients, the Bertrand Might Endowment for Hope provides a direct and effective way to do so.

If you are a patient or a caregiver, and you find yourself, as Bertrand once did, in the midst of a daunting medical odyssey, the very first article on this site is The Algorithm for Precision Medicine.

It is an overview of the process and the science that Bertrand pioneered in his brief life on the road to diagnosis and to treatments.

The rest of this site includes:

- an archive of the original site;

- information on the Bertrand Might Endowment for Hope; and

- highlights of Bertrand’s life and legacy.

The Bertrand Might Endowment for Hope at UAB

Bertrand’s life was punctuated repeatedly by the power of hope through science.

The Bertrand Might Endowment for Hope is a perpetual endowment at University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) designed to bring that hope to others, forever.

Interest on the endowment is to be used for science in the service of patients like Bertrand, and since its founding in November 2021, it has already begun to fund transfomative individualized treatments for patients in need.

(As we acquire patients' permission, we hope to tell some of their stories here.)

The permanent nature of the endowment ensures that Bertrand’s mission of helping individual patients will never come to an end.

The purpose of these funds is to cover costs of individual patients in need of:

- advanced diagnostics;

- research to identify novel therapeutic options where none exist; or

- an “n = 1” clinical trial for a single patient.

To support the Bertrand Might Endowment for Hope, please give here.

Bertrand’s life and legacy

Bertrand was a beautiful, kind, loving, happy and gentle soul to all whom knew him.

Not long after birth, Bertrand’s struggles and diagnostic odyssey began, as he faced a constellation of symptoms: seizures, movement disorder, developmental delay and an inability to make tears.

At eight months old, Bertrand’s developmental pediatrician concluded that something was wrong. It was the beginning of years of intensive medical evaluations. His medical team predicted that he would survive until age two or three at best.

In between frequent hospitalizations, Bertrand applied himself in his school and his therapy, always determined to exceed whatever limits his body had tried to impose on him: Bertrand danced; Bertrand climbed mountains; and Bertrand swam with dolphins. We’re grateful for many happy memories with him.

His body may have suffered throughout his life from NGLY1 deficiency, but neither his heart nor his spirit ever diminished or lacked for love.

Though with us for just less than thirteen years, Bertrand leaves behind a rich legacy:

2007 – 2011

At age one, Bertrand made his first pilgrimage for clinical evaluation at the NIH, visiting Dr. Constantine Stratakis for an evaluation of possible rare endocrine disorders.

At age two, Bertrand participated in a clinical trial for the use of autologous cord blood transfusion in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease at Duke University under Dr. Joanne Kurtzberg.

Bertrand traveled the country on a diagnostic odyssey seeking medical specialists that might have had any insight into what was causing his mysterious condition – or might have provided him any relief.

Finding no answers, Bertrand enrolled in a second clinical trial at Duke University under Dr. Vandana Shashi and Dr. David Goldstein – a pilot study on the use of then-novel exome sequencing to solve difficult diagnostic odysseys.

2012

At age four, the results of the exome sequencing trial were released – and Bertrand was diagnosed. The success of the trial in diagnosing patients whose diagnoses had been otherwise intractable helped pave the way for the now widespread use of clinical genomic sequencing.

In that same effort, Bertrand also became the first patient ever diagnosed with the ultra-rare genetic disorder NGLY1 deficiency, effectively discovering a new disease in the process of receiving his diagnosis.

A month later, Bertrand became the first patient to use social media in the discovery of a patient community for a novel disorder, as Bertrand’s life story went viral.

2013

- At age five, by having a confirmed genetic diagnosis, Bertrand gave the gift of both health and life to his brother-yet-to-be Winston by ensuring that he would never suffer from NGLY1 deficiency.

2014

At age six, Bertrand participated in the first patient-clinician-scientist summit for NGLY1 deficiency at Dr. Hudson Freeze’s lab at what was then Sanford-Burnham.

Later that summer, Bertrand became the first NGLY1 patient to enroll in the NIH Natural History Study for Disorders of Glycosylation under Dr. Bill Gahl, Lynne Wolfe, Dr. Christina Lam and Dr. Carlos Ferreira.

Shortly thereafter, Seth Mnookin’s article in The New Yorker chronicled Bertrand’s journey from undiagnosed to an “n of 1” to founder of an entire patient community.

Later that fall, based on evolving understanding of the disease, Bertrand began an experimental treatment of N-acetylglucosamine. It allowed him to begin producing small amounts of tears and eye moisture, sufficient to avoid a proposed surgery to sow his eyes closed and preserve his vision.

Bertrand’s N-acetylglucosamine trial was the first of several “n of 1” trials in which Bertrand participated as science continued to gain insight into his disorder. Bertrand’s key scientific collaborators in these lifelong efforts to find a treatment include Dr. Hudson Freeze, Dr. Tadashi Suzuki, Dr. Clement Chow, Dr. Kuby Balagurunathan, Dr. Ethan Perlstein, Dr. Hariprasad Vankayalapati, Dr. Yiling Bi, Dr. Eva Morava, Dr. Steve Rodems, Dr. Wei Zheng, Dr. Atena Farkhondeh, Dr. Will Byrd, the entire NCATS Translator Consortium and Beth Aselage.

After advocating for legalizing medical CBD (a marijuana extract) for the treatment of children like him, Bertrand received the first medical hemp extract license ever issued in the State of Utah.

Bertrand was then subsequently given the Purple Star Award by the Epilepsy Association of Utah for his advocacy.

2015

In January 2015, prior to the launch of President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative, the President personally conveyed to Bertrand’s father that Bertrand’s story had been an inspiration for the initiative.

Later that year, at the age of eight, Bertrand co-founded The NGLY1 Foundation, a patient support and research non-profit dedicated to NGLY1 deficiency.

Bertrand then advocated for the successful passage of the Pilot for Medically Complex Children’s Waiver Act in 2015 in Utah (which was then approved in full in 2018).

Bertrand also then successfully advocated for the passage of the Right to Try Law in the State of Utah. The law gave patients like Bertrand the “right to try” otherwise inaccessible experimental therapies. Has was personally invited by the governor to attend the signing. (In 2018, Right to Try became a federal law spanning the entire country.)

Bertrand then moved to federal advocacy: Bertrand met with Senator Orrin Hatch, asking him to be the founding Republican Senate co-chair of the bipartisan Rare Disease Congressional Caucus. Senator Hatch agreed, expanding the forum for voices of rare disease advocates to both chambers of Capitol Hill.

2016

In 2016, Bertand began attending events at The White House, starting with the Easter Egg Roll and culminating in a Scientific Meeting for NGLY1 Deficiency followed by a party at The White House bowling alley for his 9th birthday.

At age nine, Bertrand’s foundation entered into a first-of-its-kind three-way agreement with Retrophin and NCATS at the NIH to begin drug development for NGLY1 deficiency, an effort that continues moving swiftly toward treatments today.

2017

- At age ten, Bertrand finally qualified to use an eye-gaze assistive communication device, and in his final years, we began to experience a new depth to Bertrand. His vocabulary and expressiveness rose swiftly. He continued improving in his usage of his communication device through the end of his life.

2018

- Bertrand appeared in The New York Times in an article on the emergence of a strategy for fighting rare diseases inspired by his life. That strategy has been actively embodied in the Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute at UAB – and it is the strategy the Bertrand Might Endowment for Hope supports for patients. Bertrand attended several patient case review sessions at the Institute, where he could see others being helped first hand.

2019

- At age eleven, his first bout with septic shock landed Bertrand in the ICU for six weeks. After nearing death several times, Dr. Shawn Levy at HudsonAlpha conducted custom metagenomic sequencing to look for the possible pathogens driving the illness. Extending an artificial intelligence tool on the fly to analyze the data, Bertrand’s father found an unusual strain of pseudomonas as the likely culprit in Bertrand’s body. Changing treatments to match resolved the infection almost immediately, Bertrand recovered rapidly, and he swam with dolphins to celebrate just one week later. Casey Ross and Hyacinth Empinado chronicled this fight and much of his life to date in STAT [pdf available].

2020

In February 2020, at age twelve, even with his body weakening from years of ICU stays, he enrolled in an “n of 1” treatment trial at the Mayo Clinic, under Dr. Eva Morava, to begin a proposed treatment discovered by Dr. Ethan Perlstein and his team at biotech company Perlara. He passed his initial health screens to qualify, but hospitalizations immediately following his visit at Mayo coupled with the delays from the COVID-19 pandemic left him unable to start the treatment prior to his passing.

In March 2020, the same strategy and technology originally developed to find potential therapeutics for Bertrand and patients like him was applied to COVID-19, resulting in the immediate launch of a clinical trial of anti-androgen therapy for patients with COVID-19 at the VA in May 2020. (Trial results pending.)

On the day Bertrand passed, he became the first patient to donate his remains to the NIH Natural History Study for NGLY1 deficiency. Even in death, he hasn’t stopped furthering the science of his disorder.

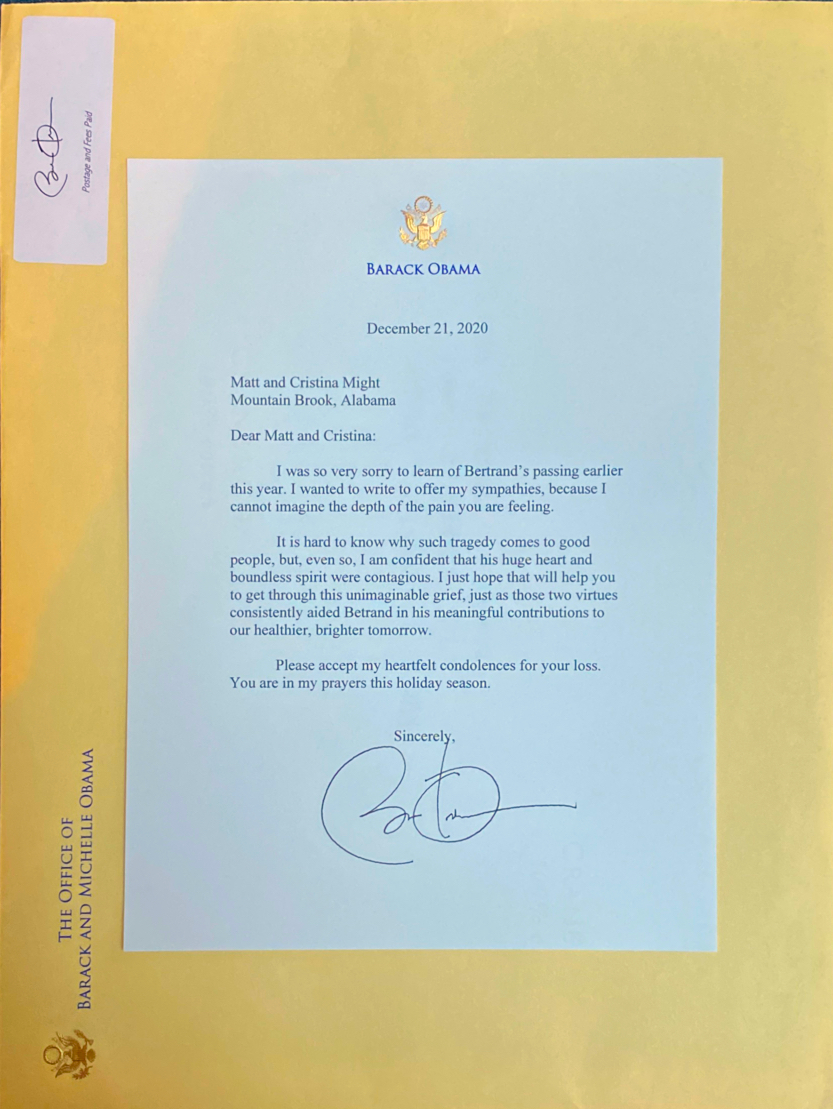

After Bertrand’s passing, President Obama personally reached out to convey his sympathies:

Archived announcement

The original announcement at the time of Bertrand’s memorial read:

It is with broken hearts that we announce the passing of Bertrand “Buddy” Might.

Happy and smiling only hours before, Bertrand progressed rapidly into septic shock on the night of Wednesday, October 21st.

Though hospitalized immediately, Bertrand declined rapidly and passed away Friday, October 23rd with the superhuman grace and dignity that had come to define his life.

While nothing eases our pain at his sudden and unexpected absence, we are grateful that he was not in pain and that he was surrounded by his loving parents all the way to the end.

We miss his courageous heart, his uncommon kindness, his quiet strength, his joyous love. We miss his infectious smile, his warm laughter, his soulful eyes.

We are proud of Bertrand’s legislative, digital, communal, medical and scientific achievements in his nearly thirteen years.

We ask that in lieu of flowers, friends of Bertrand please consider a donation to one of the causes below, which carries his impact forward.

Questions

In response to questions we’ve received:

Did he have COVID-19? No, at the time of admission to the PICU, he was negative for COVID-19 on both PCR and antibodies.

What caused the septic shock? Unfortunately, we don’t know. He was negative on the viral panels, and his cultures from time of admission never grew. Metagenomic analysis conducted during his admission was unable to complete due to the blood sample being unsuitable for sequencing.

Was he in pain? Mercifully, no. He was not in any pain for the duration of his PICU admission.